Ōtsuzumi (hip drum) & Kotsuzumi (shoulder drum)

The hip drum ōtsuzumi and the shoulder drum kotsuzumi almost always play together in alternating or interlocking patterns, and as such, they form a sort of meta-instrument. For this reason we are presenting them together.

There are five ōtsuzumi schools: Ōkura, Kanze, Ishii, Kadono and Takayasu. Featured TANIGUCHI Masatoshi and all ōtsuzumi examples are from the Ishii tradition.

There are four kotsuzumi schools: Ōkura, Kanze, Kō, and Kōsei. Featured HAYASHI Yamato and all kotsuzumi examples are from the Kō tradition.

Strokes

Strokes of the Ōtsuzumi

There are three basic sounds produced on the ōtsuzumi drum:

Strokes of the Kotsuzumi

There are four basic sounds produced on the kotsuzumi drum:

Kakegoe

Drummers alternate strokes on the drums with shouts called kakegoe. Those most frequently used by ōtsuzumi players are yo, ho, iya, yo-i, and hon-yo, whereas the kotsuzumi players use yo, ho, and iya.

The exact pronunciation of vowels and their dynamic and melodic shape vary significantly depending on the dramatic context, school and performer. Please click below to hear examples:

Ōtsuzumi Kakegoe (in the Ishii tradition)

-

ho (flexible)

-

ho (strict)

-

honyo

-

iya

-

yo (flexible)

-

yo (strict)

-

yoi

Kotsuzumi Kakegoe (in the Kō tradition)

-

ho (flexible)

-

ho (strict)

-

iya

-

iyo

-

yo (flexible)

-

yo (strict)

Each of these calls can take shape depending on context. They not only help set the mood, they are also an important communication tool, helping the musicians coordinate acceleration and slow-down. The example below is a shorter version of ashirai, played expressively for the play Aoi no ue. It illustrates how the two percussionists use kakegoe to manage changes of tempo. In the video, the ōtsuzumi and kotsuzumi alternate their calls with drumming strokes. Because the ōtsuzumi player initiates patterns, he has a leading role in establishing the tempo and mood, but both players influence each other in creating a cumulative tempo.

Rhythmic Organization

Strict and Flexible

The drum parts are connected to the eight-beat measure. We call a rhythmic setting 'strict' when the beat is relatively steady and 'flexible' when the beat is irregular. In the latter case, the music is often characterized by fewer strokes and a slower tempo. The difference between the two rhythmic settings is also accentuated by the kakegoe. In strict setting, the calls are centered between beats and have a shorter, more accented quality. In flexible setting, the calls start earlier and can extend for the duration between beats. Percussion parts in a flexible rhythmic setting are performed primarily by the ōtsuzumi and kotsuzumi since most of the music involving the taiko is strict.

For comparison, an Ashirai sequence of four eight-beat measures is performed in a strict and flexible setting.

Patterns

The percussionists’ strokes and kakegoe are arranged into patterns of varying duration—as short as two and as long as thirty-two beats. Patterns are then sequenced to produce longer phrases. Although the ōtsuzumi and kotsuzumi have their own set of patterns, they usually work as a pair. When accompanying singers, their individual patterns interlock and complement each other to form a single combined eight-beat pattern. The ōtsuzumi, with its louder sound, is usually more active within the first four of the eight beats, while the softer kotsuzumi picks up in the last four. This creates a continuous fluctuation of color and intensity. The combined patterns typically start on the upbeat leading to the first beat of the eight-beat unit (honji).

For both instruments, there are several categories of patterns of which we will cover the most prevalent two, ground and closing. The majority of ground patterns fall into two different types: mitsuji and tsuzuke.

Mitsuji

Mitsuji patterns are characterized by a smaller number of strokes and a degree of rhythmic ambiguity that increases the dependence on kakegoe to maintain cohesion. They can be performed in strict or flexible rhythmic setting as shown in the following examples:

Tsuzuke

Tsuzuke patterns are characterized by a larger number of strokes and relative rhythmic stability. The respective patterns of the two instruments spread and interlock to cover the entire eight-beat unit. They can be performed in a strict or flexible rhythmic setting, as shown in the following examples:

Mixed Sequence

The sequencing of mitsuji and tsuzuke patterns creates phrases whose rhythm moves like waves: from rhythmic ambiguity created by the sporadic attacks of the mitsuji pattern, to rhythmic clarity coming from the steadier tsuzuke patterns, and back to ambiguity with the beginning of the next phrase’s mitsuji patterns.

In this context, five observations can be made:

1. The two percussion instruments have a large selection of

mitsuji and tsuzuke patterns (well beyond the few

provided examples). In our narrative, we have used these terms

broadly: mitsuji for an eight-beat measure (honji)

articulated with a limited number of strokes, and tsuzuke for

a honji articulated typically with one stroke per beat.

2. Rhythmic phrases always begin with a mitsuji pattern

leading to a tsuzuke, which either leads to a cadential

pattern or to another phrase: mitsuji –

tsuzuke sequence.

3. The ratio of mitsuji to tsuzuke in a phrase

affects its overall rhythmic stability. Phrases with more

mitsuji patterns have a higher degree of rhythmic ambiguity,

while phrases with more tsuzuke patterns have a higher degree

of rhythmic stability.

4. The degree of rhythmic stability/ambiguity of a phrase is also

impacted by its rhythmic setting, where a strict setting is more

stable than a flexible one.

5. The sparse mitsuji patterns are most often used to

accompany a chant set in the declamatory

mitsuji-utai. The limited number of percussion strokes is counter-balanced by the

melodic line unfolding with few or no rests. On the other hand, the

regular tsuzuke patterns are most often used to accompany a

chant set in the

tsuzuke-utai, where syllables held over to accommodate the measure’s eight beats

create rest in the melodic line counter-balanced by the steady

percussion strokes.

The following two videos show strict and flexible setting of a mixed sequence. Each version begins with four repetitions of a mitsuji pattern followed by one tsuzuke.

Uchikiri pattern

Uchikiri pattern is often used as a bridge to reestablish a strict rhythmic setting after a flexible module (shōdan) or after a very slow, strict one. It often leads to shōdan with a strict rhythmic setting such as Ageuta, Kuse, or Sageuta. It is easily recognizable by the ōtsuzumi player’s kakegoe "ha hon yo". In this video, the excerpt is extended to include the first beat of the following phrase.

Entrance and Dance music

When performing dances, Noriji, and some entrance music, the musicians maintain complementarity between the two hand drums despite the fact that they perform patterns of different length. This is demonstrated in the following excerpts from the dance Jonomai. In this example the kotsuzumi’s nagaji pattern is spread over sixteen-beats against the ōtsuzumi's ji pattern that lasts eight-beat.

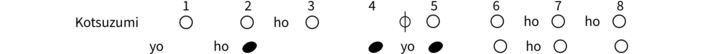

Kotsuzumi's nagaji sixteen-beat pattern:

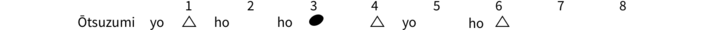

Ōtsuzumi's ji eight-beat pattern:

Another noteworthy point is how the ōtsuzumi's closing (shikake) pattern breaks the predictability of the repeated patterns. Its steady six strokes and subsequent kakegoe announce the end of the dance and initiate a cadential deccelerando.